Democratizing Innovation

“Users that innovate can develop exactly what they want, rather than relying on manufacturers to act as their (often very imperfect) agents.”

Democratizing Innovation

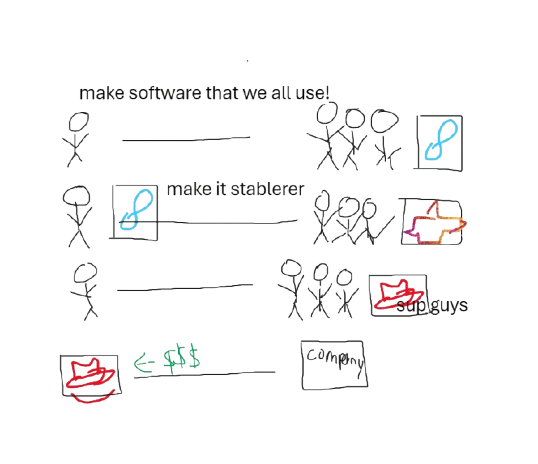

The quote is the central thesis of the book. Hippel here is writing against the dominant narrative of R&D, a narrative that supposes the core of innovation lies in the operation of manufacturing firms that produce and construct goods. Users in this story have no innovative power outside of voicing their needs or commanding their Capital on the market.

Hippel essentially says to the R&D industry: “You’ve got it all wrong!”. It is precisely the users of the goods that are the innovators. Users are the ones making the product better and generating new features, not the manufacturers. This point might seem obvious now, given the sort of shift and movement towards UX design. But no, product managers back then, and maybe still even now, point to their R&D department as the core product innovators.

I took an interest in this book precisely because of its relation to the open-source community. I mean, there’s no way a book titled Democratizing Innovation does not highlight the shifting effects of information technology and its effects on transacting user knowledge openly and effectively.

It does. Interestingly, though, it didn’t cover the likes of GitHub 1. It covered SourceForge, qt and KDE, GNU, Apache, Red Hat, and StataCorp, all with shocking relevance to what is seen now in the open-source community and the continuation of the same user-manufacturer shenanigans that went on back then. So, for my reflection, I want to map Hippel’s theory and explore its idiosyncrasies with real-life case studies.

Red Hat & CentOS

Ironically enough, when Hippel is discussing manufacturer firms and ways to work with user innovation in software, he points to Red Hat Enterprise Linux, which, after 13 or so years, has been acquired by IBM and stirred up quite a lot of controversy.

They have gone to the side of being a manufacturer instead of a user firm and have been described as “egregiously bastardizing open-source contributors by profiting off of their efforts”2. But going back to when Hippel wrote this text, he highlighted how Red Hat as a firm dealt with monetizing open-source with respect to providing technical support for the project.

”(3) Manufacturers may sell products or services that are complementary to user-developed innovations.”

Democratizing Innovation

This monetization model was reasonably uncontroversial. You have a group of users contributing to an OS for the use of each other without any care for funding. Then you have Red Hat that takes this OS and contributes to it as well, but also says: “If anyone wants to support, you can get it from us.”

The concern was when they decided they would go and make their upstream version behind a paywall. This move modified their relation to the users as more of a user-to-manufacturer than a user-to-user.

The decision can be interpreted as Red Hat supplanting itself on top of the open-source community, similar to what Amazon did to ElasticSearch. In the end, though, it feels more complex than that.

On the one hand, a case can be made that Red Hat being profitable is suitable for open-source because it means that user innovators can get paid explicitly for what they do by Red Hat. On the other hand, there is still the argument that this corporation’s supplanting is a net negative to the ethos of the open-source community.

The answer Hippel gives is likely along the lines of this. Individual users are mainly unaffected aside from being suspect towards the profit motive and the ethos around “enterprising” the project. User firms are generally outraged because they now have to pay for either the license for RHEL or using CentOS Stream.

Red Hat still offers services technical support, fixes, updates, and services while (hopefully) contributing back to the open-source ecosystem. The tension, however, lies in whether this compromise tips too far toward commercialization, risking the alienation of the very community that sustains open-source innovation 3.

Hashicorps Move to BSL

The story here is that the tooling under Hashicorp was deemed “open-source,” much like Vagrant before Hashicorp was created as an entity. The users or user firms were able to openly commit to the source code of any of the Hashicorp tools like Terraform, Helm, Consul, etc.

The backlash occurred when they tried to shift over to a BSL license, which meant that their status was now more of a manufacturer than an open-source community. It follows a similar pattern to the whole open-source -> enterprise edition firm. This incompatibility stems from the conversion of user innovation to a firm status, creating a contradiction of the general open-source ethos.

I thought that Hashicorp was acting like an open-source organization that held these projects without the goal of profiting from them. But really, why is this open-source enterprise business model causing so much drama?

Similar to RHEL, the developer firms contribute to the open-source and benefit from user contributions. Then, they go on to offer an enterprise edition that is aimed not at users but at user firms. These developer firms ostensibly profit from commercialization via enterprise editions, which are large sums.

My summary of understanding this debacle is found in two questions. The individual user asks why this project needs to be enterprise-level, and the firm user asks why I should pay for this “open-source” project. Enterprise Open Source is more of a CYA purchase than anything akin to hiring consultants.

Keeb Community

The mechanical keyboard community, shortened keeb, is an example that immediately came to mind for me when Hippel was discussing how physical product manufacturers can work with users by taking the side-line to product development and instead focusing on producing parts for the community.

The manufacturer’s role here is to take the user-developed innovations in the keyboard community and do what they do with economies of scale to produce the base parts of kits that the users purchase. This story is what happened in the keyboard space. Manufacturers are following the rules Hippel as set out:

“(1) Manufacturers may produce user-developed innovations for general commercial sale and/or offer a custom manufacturing service to specific users. (2) Manufacturers may sell kits of product-design tools and/or “product platforms” to ease users’ innovation-related tasks.”

Democratizing Innovation

Many popular keyboard manufacturers, like DROP or KBDFans, sell fully functional keyboards themselves, but they mainly rose due to their manufacturing of keyboard kits. The design of these keyboard parts and of “what” to build is largely left up to the community innovators to generate.

They sell (1) the custom keyboard specifications on their website along with (2) entire kits or parts that the user can go on to build the keyboard for themselves. Besides the manufacturer narrative fitting, the user narrative is about the same as well.

Users of keyboards make modifications for aesthetical and functional reasons like the sound, sight, or feel of the keyboard. This matches what Hippel writes on the reasons users innovate, which is the heterogeneity of needs that transcend simple market segmentation. On top of these diverse user needs, the construction of keyboards themselves allows for hobbyist intervention.

Similar to how old Thinkpad laptops and their parts are praised for their modularity, the same can be said of mechanical keyboards. The case, PCB, plate, switches, stabilizers, and keycaps are all different interchangeable parts in a keyboard. All of these effects coalesce into substantially healthy user-manufacturer relations.

Samsung Electronics

The case study that throws a monkey wrench into Hipell’s theory. It doesn’t seem like the case here that the user innovators or the firms using microchips are the ones innovating in the manufacturing process. And the reason why was probably already covered in the book; I need to look for it.

My theory behind it uses Hippel’s highlight of software’s unique characteristics of transactive and production costs; It’s practically speaking 0. In contrast with the semiconductor industry, the barrier to entry is so much higher that users cannot innovate. Apple or any hobbyist does not have access to billions of dollars to innovate on chip manufacturing at their whim.

“Freedom from manufacturer involvement is possible because information products can be “produced” and distributed by users essentially for free on the web (Kollock 1999). In contrast, the production and diffusion of physical products involve activities with significant economies of scale.”

Democratizing Innovation

Conclusion

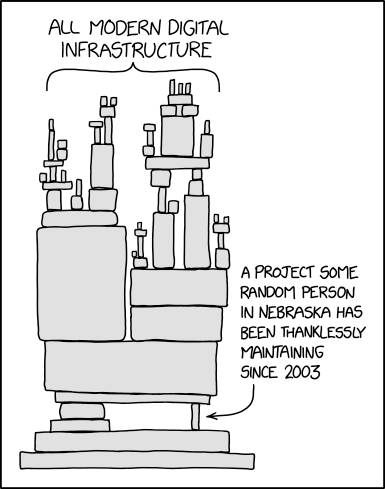

Hippel gives us an insight into the nature of production in information products vs. physical products. If you take it that Code is a form of Capital in the new age, traditional views of the manufacturer really have little power or control over information products that are developed, shipped, and diffused in the realm of open-source.

I mean, really, looking at the history of open-source and software products in general, they have always ended up being democratized. UNIX became proprietary, and Stallman et al. went out to develop their own POSIX-compliant code base. LibreOffice being made as an open-source version of Microsoft Office. The list of FOSS has gotten to the point that you really don’t need to pay for any user-based software.

There was less discussion on noneconomic extrinsic motivators than I had wanted. Still, given the fact that the capital economy is how we coordinate social welfare, it would have to be/been 100% academic suicide to tack on the point that open-source software could be “socialist” or pejoratively “communist.” A discussion on the institutional actors doesn’t need to inquire into that.

I do like that aspect when discussing the more behavioral aspects of institutional actors, the behavior of firms, or “business entities.” But still, there is the undeniable existence of an ideological ethos that divides user-firm innovators and user innovators, along with their propensity to share.

In the end, this all hearkens back to a controversial distinction: free or open source?