gentrification, cville, development, uva

The city of Charlottesville can be considered gentrified. But what does the term gentrified even mean at this point? We all hear it being thrown around as a pejorative against the historical and ongoing development of a place. The evocation of gentrification, or any pejorative really, usually comes with an ethical judgment and epistemic closure. Subsequently, we (or at least I) fail to trace out the viewpoints of the developers by casting them as essentially evil, but also, on the flip side, fail to understand the deep ways in which development affects the existing people.12

Before going any further, this post was made for a midterm assignment for one of my classes. However, the goal of this post is for me to critically assess the histories and ongoing stories of development in Charlottesville. This blog post serves to help me address questions I have about the place where I’m earning my degree and the institution’s position within everything.

The questions I will go on to address in this blog are as follows:

- What happened at and to Vinegar Hill?

- What are the implications of the University being AAA bond-rated?

Vinegar Hill

Vinegar Hill is the case of inequitable development. It makes clear what I felt unease about when looking into the debate around gentrification: Who controls development? Who benefits from development? It is not just development as an overloaded term, but also taking a look at how politics plays out and the bodies that experience it.

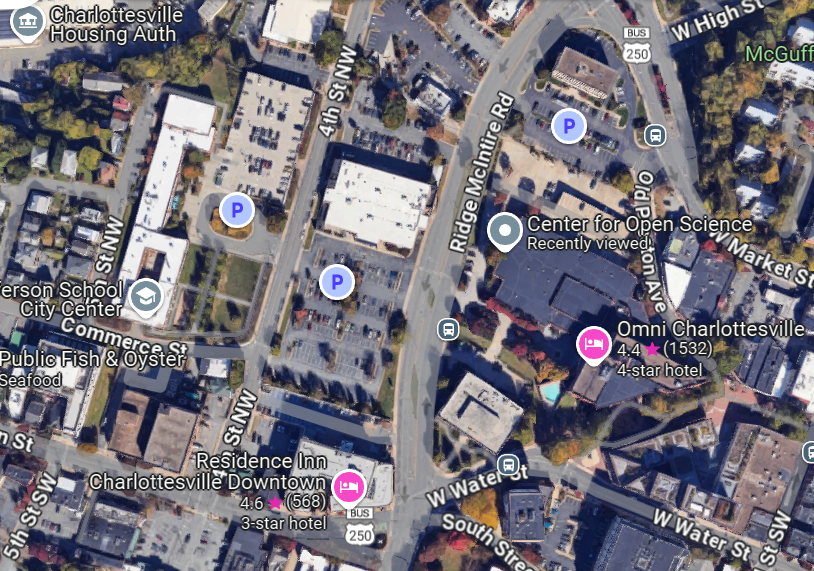

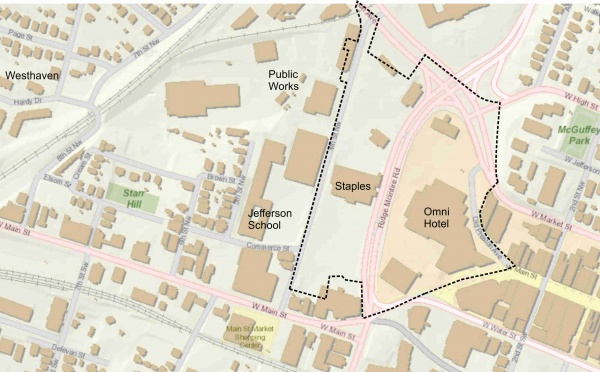

I want to start with what Vinegar Hill has been like in the 21st century. Taking a look down from the intersection connecting downtown, you can see a Staples, the Omni Hotel, and a U.S. Federal Building. Should this be called a success? The Omni does bring in a lot of tourists with money into Charlottesville, and it being situated downtown only adds more to the economic solidification of the building. But what happened to the people? The 600 residents and 30 businesses.

The 600 residents and 30 businesses inhabited Vinegar Hill in the 1900s. Archival information, which there is not a lot of, shows that the place was indeed vibrant and economically active (generated $1.6 million annually not sure if scaled for inflation). However, not everyone saw Vinegar Hill in such a light. Due to Vinegar Hill’s adjacency to the downtown area, it got a lot of public attention and was constantly denounced as a “blighted” area. And yes, there were racial undertones to how Vinegar Hill was conceived of as a place and contributed to its excision from Charlottesville.

In a 1960 transcript from Charlottesville Daily Progress, a local banker gave his take on the proposal for urban renewal:

“Haden said, when asked what effect he thought the program would have on downtown Charlottesville, “I believe it will be helpful. As everybody knows, our business section of the city has been divided largely into two sections-the University section and the downtown section. This Vinegar Hill area has been all my life a very blighted area and it seems to me that if the situation is corrected, the whole business area of Charlottesville will be much helped.””

Why not, instead of “correcting” Vinegar Hill by demolishing it, invest in Vinegar Hill? The answer to my question is racial politics and how it systematically limited economic access to Black people. The history of redlining and risk classification based on stereotypes were levied against them to prevent any access to economic/financial instruments.

In the case of Vinegar Hill, this was no different. Urban renewal meant the wholesale destruction of their properties and businesses for the development of White business owners. Urban renewal meant they were forced out of their homes and relocated to public housing without being compensated. Urban renewal was never for the Black community on Vinegar Hill.

What I gathered from Vinegar Hill is what happens when there is an imbalance in development. What happened at Vinegar Hill is a story of inequitable development and gentrification. Where the inhabitants of a place had no say in the matter, no voice, and no real political power to state themselves. The case brought to light how inextricably politics is bound up with economics and has profound impacts on the ways politics can legitimize itself to do harm. The real kicker is when I found out how the land was taken: by eminent domain and White voters.

5 years before the demolition actually occurred. A guy named Lipset wrote on Social Prerequisites of Democracy. Relating it with the case of Vinegar Hill made me wonder if the paper addressed race relations? From the viewpoint of the White developers, Democracy was working great. They had systems of economic development education, income equality, and an ongoing project of urban renewal. On top of that, the people of Charlottesville were checking off the boxes for democratic values like civic engagement and legitimizing institutions.

This same emphatic blind spot for those in power seems to remain at the forefront of modern development discourse. It makes sense though, because as the systematic structures and normalized beliefs become invisible, the only thing left to say is: “Why don’t they just have it figured out like us?”. It echoes a similar viewpoint from the DFID paper, where they discovered inequality of assets affects the distribution of development but had nothing to say on how the inequality came to be and how to concretely address it.

Closing up the Vinegar Hill section, I have a bit of hope as something egregious as this only occurs when you justify economic development and view a group as less than human / deserve zero social capital. I think the US has, at large, moved past the whole racism thing? Keeping this case study in mind, I want to turn towards the future and ongoing histories of development at UVA. Though the university is also haunted by its past involvements in similar displacement stories of Gospel Hill and Canada, I want to inspect the university in the present. What does it mean to attend a university that advertises human and political development but actively prides itself on having AAA bond ratings?

UVA and Development

What does it mean to attend a school that sells bonds? It means that I, as a student, am a financial object for the university. To that extent, I am only a part of the economic calculus of UVA to grow. Really, I get a deep sense of anxiety as it’s a pretty depressing line to go down. Because the implication is clear, a neoliberal university will only have to meet the status quo and maintain appearances in order for it to “survive.” I’m not saying economics is not important; I’m saying that when it ends up subsuming everything else, then it might become a problem. It is clear that the university values the continuation of development, but it’s mainly a question of to what end.

Rehashing a quote from Amartya Sen:

“The ends and means of development call for placing the perspective of

freedomcapital at the center of the stage.”Development as Freedoms

Just reflecting on my own biases, I ask this question: Why is the pragmatic man viewed as better than the ivory tower man? They are both extreme cases. But one of them intuitively feels more good than the other. So which of the two does UVA produce, and for who? Currently, it would be no stretch of the imagination to say that universities produce for the sectors. This production story is being played out in real-time, with the trending majors correlating 1:1 with the trending jobs on the market.

I mean, there is no hiding it: the goal of the university is to be economically and commercially practical. Not to argue for the ivory tower, but I think not everything should be pragmatic. The point of theory is that it can be made practical. Higher education should not be solely focused on pragmatics; it must also nurture creativity and intellectual curiosity, empowering students to question assumptions and drive meaningful social change beyond mere economic outcomes.

So when something like v is said for our 2030 plan; I’m extremely skeptical.

“In all this, we must never forget that our ultimate purpose, especially as a public university, is to serve the public through an unending and fearless search for truth and through our teaching, our research, and our health care.”

Especially when it was prefaced with

“In 2030, universities will be judged in part by how well they are run and whether they are ethical institutions— whether they are great places to work and good partners with their surrounding communities; whether they are engines of economic growth; and whether they reach students, of any age or walk of life, who do not have the good fortune to enroll as full-time students. Attention will be paid to the return on investment, whether it is the investment that families make when paying tuition or the investment that legislatures make when allocating funds to support universities.”

Given my pessimism, but also seemingly wishful thinking for higher education, I want to make space for the future. Aren’t we students bringing in these values and beliefs toward what we want from the university? The optimism here is that really the university does not have any choice but to play by these games of growing endowment funds, getting research grants, and practically teaching workable skills. I’m optimistic because we are the students that make up the institution! I think we have some say? Okay, I was motivated for a second, but it faded away. Why? Thinking back to Vinegar Hill when economic development was achieved through disregarding human/political dimensions, the same is happening here, just more subtle and less racist. UVA doesn’t care as long as it gets paid.3

What I Think of Development

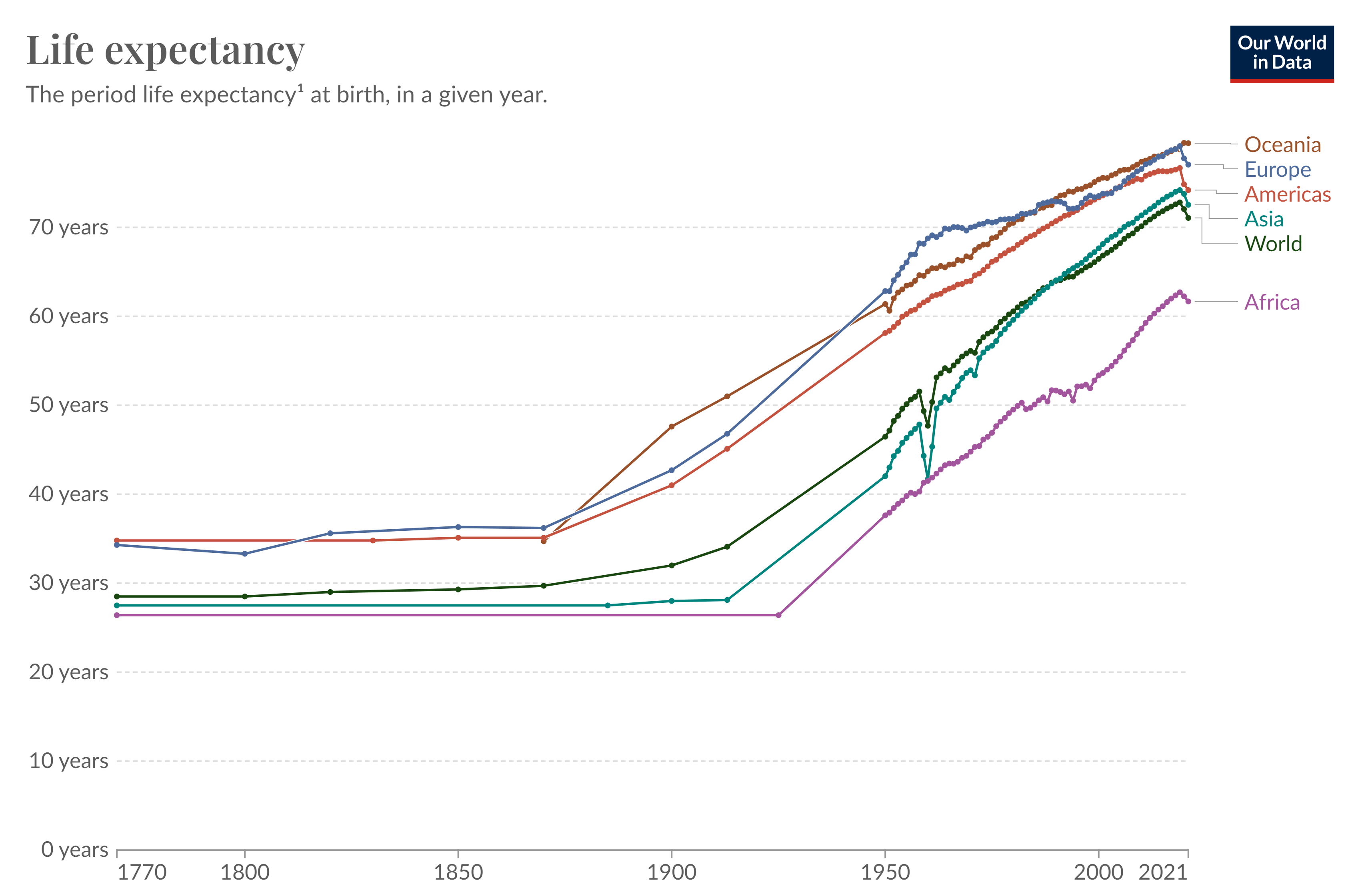

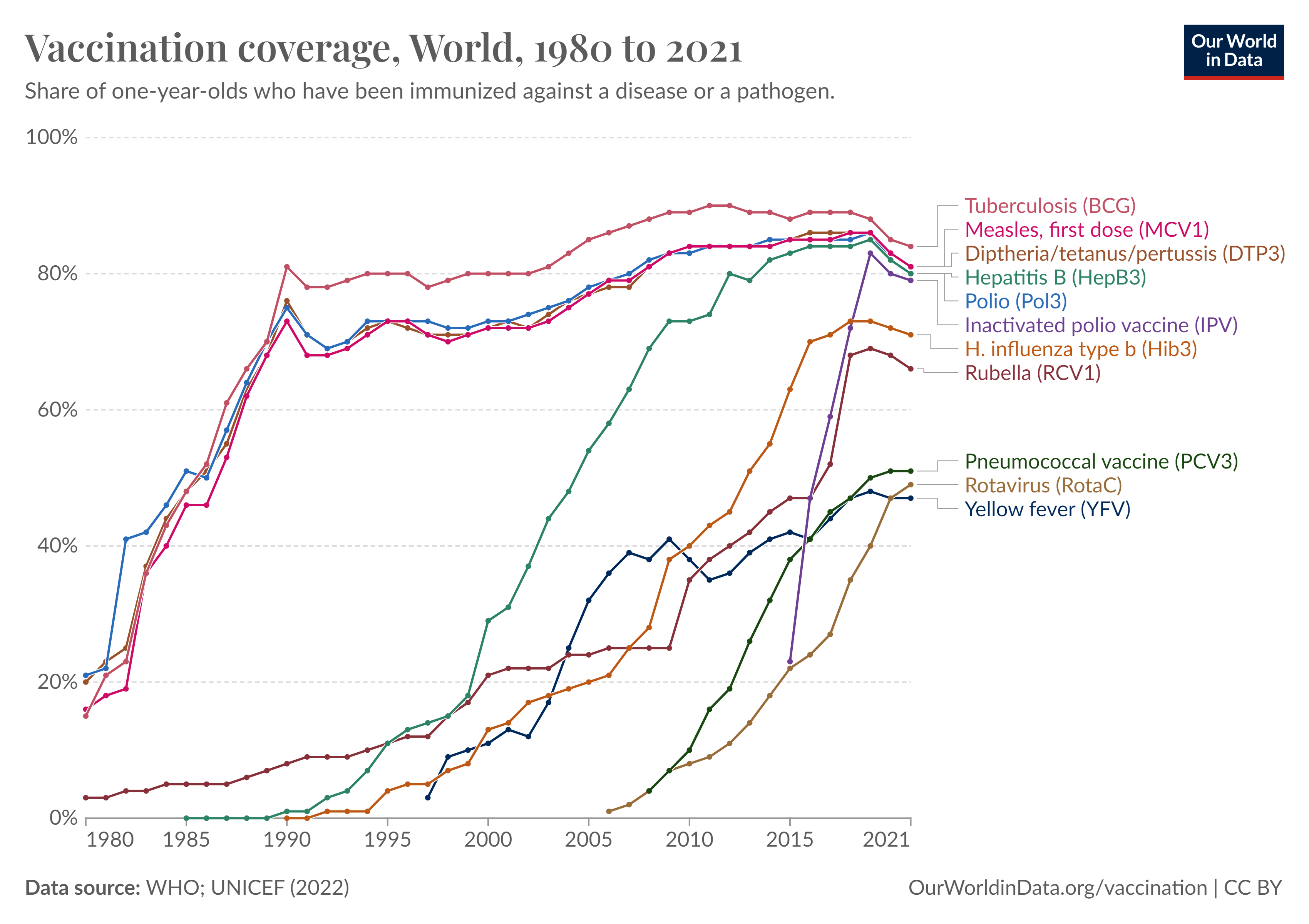

Despite everything I have said, I’m hopeful. Development as a project historically has, in my view, taken some wrong turns and often veering way off-course. The hard part in outright rejecting it is that there has been good that has come of it. Even if it required enslaved people or the many, many horrendous, inhumane, unethical steps here…

I think this is why, in class, the question of if inequality is a problem is posed. At face value, yes. However, the output of colonialism was massive improvements in technologies, which has been shown in the data to have made “everyone” better off. Obviously, it is still a problem. But, there is a more profound truth to be teased out.

My own reflections on development after doing the case studies are as follows:

- development as process (how its done): should be inclusive and participatory

- development as project (what is done): should be ethically goal committed

- development as a study (ways to approach it): should be interdisciplinary

The implication, then, is that I will involve everyone in the development process, continually evaluate the ends development accomplishes, and openly consider different perspectives on development.

Post Blog Reflections4:

I keep reflecting more on this blog and want to rewrite or add pages of notes/edits. That’s why I made this section, so I don’t… Anything new or interesting will be added here.

I found an interesting video essay that aligned with a lot of the notes here. What they do different is highlight the “facile liberals”/”champagne marxists”, NIMBYism (not-in-my-backyard), through using Berkeley as an example of how left-wing/progressive position holders can still reify class inequality, even willfully at times. The first 20-30 minutes or so focus on critiques of gentrification as a term, its history, and who it affects.

After reading more about the Berkely situation, I found it funny how the history of development at Berkely is the reverse of UVA’s. Berkely first established itself there and attracted people to buy up land surrounding it. Now, they don’t want the university to build more housing. UVA was not the “first to be here;” instead, it expanded by actively buying out land to develop. But in our case, building affordable housing does not absolve UVA of its history of acquiring the land.

Citations

Cameron, Brian. “UVA And the History of Race: Property and Power.” UVA Today, 15 Mar. 2021, news.virginia.edu/content/uva-and-history-race-property-and-power.

Charlottesville Archive. www2.iath.virginia.edu/schwartz/archive.html.

Charlottesville Archive-Texts. www2.iath.virginia.edu/schwartz/texts.html.

DFID. “Growth: Building Jobs and Prosperity in Developing Countries.”

Ghertner, D. Asher. 2015. “Why Gentrification Theory Fails in Much of the World.” City 19 (4): 552–63. doi:10.1080/13604813.2015.1051745.

Lipset, Seymour Martin. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” American Political Science Review, vol. 53, no. 1, Mar. 1959, pp. 69–105. https://doi.org/10.2307/1951731.

“The Neo-Liberal University on JSTOR.” www.jstor.org. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40342886.

Progress Timeline: Advancing Our Goals. strategicplan.virginia.edu/vision.

Rose, D. “Rethinking Gentrification: Beyond the Uneven Development of Marxist Urban Theory.” Environment and Planning D Society and Space, vol. 2, no. 1, Mar. 1984, pp. 47–74. https://doi.org/10.1068/d020047.

Roser, Max. “The Short History of Global Living Conditions and Why It Matters That We Know It.” Our World in Data, 19 Mar. 2024, ourworldindata.org/a-history-of-global-living-conditions?linkId=62571595.

Sen, Amartya Kumar. Development as Freedom. 1999, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA43059927.

Smith, Neil. “Gentrification and the Rent Gap.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 77, no. 3, Sept. 1987, pp. 462–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1987.tb00171.x.

Urban Renewal, Vinegar Hill, 1960, Charlottesville Daily Progress Articles. edu.lva.virginia.gov/dbva/items/show/300.

Zuk, M., Bierbaum, A. H., Chapple, K., Gorska, K., & Loukaitou-Sideris, A. 2018. Gentrification, Displacement, and the Role of Public Investment. Journal of Planning Literature, 33(1), 31-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412217716439

-

After reading some literature, I am conflicted about my interpretations of gentrification. There are 10+ different definitions, ways of measuring, and viewpoints on it, which makes it even more confusing. ↩

-

I’m glad I’m not crazy, doing some more reading. There have been many critiques against the broad field of gentrification theory due to the overloading of the term. For the purpose of this blog, my definition is just the existence of class/racial re/displacement. I say existence because it would be intellectually disingenuous for me to provide a definition that covers the processes of gentrification. ↩

-

It’s a pretty fatalistic ending to the paragraph, but I’m still hopeful. ↩

-

For grading purposes, please ignore this section ↩

-

My final takeaway on gentrification is that it’s actually caused by speculation, not any physical environmental changes. ↩

-

Vienna, Austria, the birthplace of Austrian Economics, has 80% social housing? ↩